Canada Has Changed

As the Harper decade comes to a close, it is clear that Canada has changed.

This is no surprise. Any political party that governs for a decade is unlikely to leave a country as it was found.

Nor is change bad. Indeed, Canada’s history demonstrates our willingness to change, to grow, and to adapt to new challenges and circumstances.

Today, Canada is a flourishing and proud multicultural nation. Comprised of immigrants and Indigenous peoples, we’ve created a unique and dynamic country built upon a foundation of compromise, deliberation, and humility.

But over the past ten years, under the governance of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister Harper, Canada has been turned inwards. The foundation that once grounded us has eroded, and the ideals that for generations guided and defined us have been corrupted.

Canadians of all stripes feel it — a creeping sense that we’ve lost our way, or that our collective sense of self has been distorted. The Harper Decade represents an attempt to dissect the past ten years, and to discover just what has changed.

A number of disturbing trends have emerged.

Canada has become more diverse, but less inclusive.

Canadian identity is tied up with the notion that we are a tolerant and inclusive society that not only welcomes individuals with diverse backgrounds and outlooks, but openly celebrates and encourages them. This understanding is informed by a number of measures, including statistics on linguistic and ethno-cultural groups in Canada, and the extent to which our legal system protects and supports minority rights and freedoms. Each successive Canadian generation is more diverse than the last, with greater protections afforded to minority groups to maintain their unique identities. This trend has continued even during the Harper decade, despite the efforts of the federal government to reverse it.

The Conservatives have erected laws and created policies that not only restrict and weaken the rights of minority groups in Canada, but also ensure that Canada becomes a less diverse and accommodating place. Canadian immigration and refugee policy has been overhauled. New barriers now prevent immigrants from attaining citizenship, while our temporary foreign worker program, which offers no clear pathway for permanent residency, has been dramatically expanded. Family reunification is now reserved for the affluent and well-established. Similarly, the Harper government has made it far more difficult to seek refuge in Canada. Refugee claimants who do make it to Canada often find themselves without basic rights or protections.

The government’s efforts to restrict migration to Canada has been paired with consistent messaging designed to mask the discriminatory aspects of these laws and policies with concerns over national security, Canadian values, and the limits of our social welfare system. They were also the source of international scandal this fall, when it was revealed that the Harper government had halted the processing of United Nations-referred refugees for extra screening based on their ethnic and religious backgrounds.

The Harper government has gone even further by seeking to restrict and diminish the rights and freedoms of individuals in Canada on the basis of their ethnicity. The most consistent target of the federal government’s strategy has been Muslims. The niqab controversy is one of many policies aggressively promoted by the Harper government to sow xenophobic fears of outsiders for short-term political gain. However, this divisive, wedge approach to politics has not been exclusively directed towards Muslim communities in Canada. Other groups, including Roma refugees — who came under attack after being categorically defined as “bogus” for no other reason but being Roma — have also been targeted by the Conservatives.

With the passage of Bill C-24, the Harper government has even enacted tiered citizenship, according to which the extent of one’s citizenship rights are now informed by their country of origin, nationality or ethnic background. Citizenship, once a right, now becomes a privilege, and in the process, is stripped of the notion of equality that serves as its foundation.

Prime Minister Harper has also neglected the broken relationship between Indigenous peoples and the federal government. Indeed, it’s been argued that the Harper government is one of the most racist and aggressive governments that Indigenous communities have had to work with in many generations. Though Indigenous groups have achieved several hard-fought victories in the courts over the past decade, the federal government has failed to address the major socio-economic gaps that divide Indigenous peoples and mainstream Canadians. Further, the government has shirked its responsibility to consult with Indigenous communities before approving industrial projects on their land. Resistance to industrial development has been suppressed, while Indigenous activists have been portrayed as eco-terrorists and targeted for surveillance. Finally, Harper has ignored persistent calls for an inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. In late 2014, Harper demonstrated his lack of empathy towards the issue by declaring that dealing with the phenomena of missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women “isn’t really high on [his government’s] radar.”

However, the Supreme Court has proved remarkably consistent in ruling against government legislation, and for Aboriginal and minority rights, even as Harper-appointed justices formed a majority of the bench and the government encouraged an increasingly partisan narrative of legal challenges to their policies. Emerging from the decade unscathed, the Supreme Court continues the essential work of defending Canadians’ rights and freedoms under the Charter.

The challenges we face today are larger and more complex, but our approach has become less imaginative.

Over the course of the Harper decade, Canada has adopted retrograde public policies in a number of key areas, including immigration and criminal justice. Impending national crises stemming from our aging population, such as rising costs for social security and end of life care, have been left unaddressed. Any innovations that have occurred, such as the ‘Housing First’ strategy, have been hampered by a social welfare system that has not kept up with changing demands or increased costs.

At the heart of Canadian policy making are public servants and bureaucrats. We count on their expertise and experience to guide our elected representatives and to make sure that high levels of non-partisan research and services are accessible to all Canadians. However, under the Harper government, we have seen the rise of an increasingly partisan bureaucracy. This is not to suggest that hiring has been explicitly partisan, but that the nature of the public service has been changed such that it no longer attracts top talent or allows public servants to work effectively. Many departments have undergone a new prioritization of industry interests over public safety or environmental protection, with corresponding cuts to their research capacities. Other departments have been hampered by the loss of the long form census and cuts to Statistics Canada. And all departments and public servants, including researchers and scientists, have faced increasing interference from the PMO in communicating their findings with the Canadian public.

When it comes to environmental issues, Canada has recently become an outlier. Even as countries around the world, including the U.S. and China (the two largest emitters), have acknowledged the effects of climate change and taken steps towards curbing greenhouse gas emissions, Canada has refused to engage substantively in international climate discussions and was the only country in the world to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol. Instead of seeking creative ways to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, the government has focused on tearing down any barriers to resource extraction and silencing environmental critics.

Canada has also failed to create a robust economy capable of weathering the shocks of the extractive industry’s boom and bust cycle. Our reliance on oil has backfired as the industry grapples with record low prices. Indeed, the past decade has proven that Canada is vulnerable to complex economic issues often outside of our control. Harper’s narrow fiscal policy has stripped the government of the flexibility required to address these challenges.

Harper has won praise for shelling out individual boutique tax credits and lowering corporate tax rates. But by reducing taxes and constantly advocating for a balanced budget, the government has effectively starved itself for the future – making it impossible for the government to mobilize and respond effectively in times of economic crisis.

Our national dialogue has shifted from placing an emphasis on the actual purpose of public policies, to the question of how much they will cost. Boosting economic growth, diversifying our economy, addressing pressing social issues like poverty (1 in 7 Canadians, including over 540,000 children, live below the poverty line), homelessness, and food insecurity – these challenges require a national vision and creative fiscal planning, not just tax credits for politically targeted groups.

On security issues, Canada has also been forced to reckon with increasingly complex threats — potential and realized. Yet, Harper’s security and surveillance strategies, from protecting the arctic to preventing terrorism, have emphasized fear, nationalism and secrecy above efficiency, efficacy, and the integrity of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Surveillance policy, for example, has seen bills introduced to great fanfare, designed, ostensibly, to protect Canadians from child pornography, online bullying, and terrorism, only to die quiet deaths at the end of a parliamentary session or be struck down by the courts. Effective policy doesn't seem to be the point — demonizing opposing parties during debate and filling party coffers is. And despite national protests sparked by justifiable fears that the government would use Bill C-51 to spy on Canadians rather than prevent terrorism, the controversial legislation was passed (and already faces court challenges). It seems that surveillance policy is less about securing the country than securing the governing party through intimidation.

Rarely is security an issue of good versus evil, easily addressed by military or police intervention, despite what government messaging would lead us to believe. Strong social programming, robust immigration and refugee policies, and international cooperation are just as much a part of securing the future for Canadians.

We’ve put ideological values above evidence-based policy. As a result, we are far less informed.

While Canadians enjoy unprecedented access to information and use it to make decisions on everything from grocery shopping to personal health care, the Harper government has reduced access to vital data and scientific research – making citizens less informed and governance less effective.

When we look back on the Harper decade, the abolition of the long-form census in 2010 is consistently referenced as a landmark decision that has irrevocably disrupted our understanding of Canada. Thousands of organizations, both public and private, depend on the decades of information collected by the long-form census to operate effectively. From businesses making investment decisions to charities assessing the needs of their communities — these groups have spoken out in frustration about the now unreliable data, or in some cases, the lack of any data at all.

But we are most concerned with the impacts on research and policy making. As our commentators suggest, by failing to collect accurate, comprehensive data on Canadians, both the government and citizens are unable to identify where and when our policies fall short of adequately addressing issues of poverty and public health, or make informed decisions on how to improve government services.

The loss of the long-form census is part of a broader trend to reduce access to information to the advantage of those more interested in pushing politicized talking points. Cuts to public service jobs and federal research funding have hampered national scientific research, while scientists that remain a part of the public service are prevented from speaking directly to the public about their findings without approval from the PMO. One report found that “over half of federal scientists [were] aware of cases where the health and safety of Canadians has been compromised because of political interference.”

The Harper Decade series has touched on a number of other examples where politics have been prioritized over the imperative to keep Canadians informed. Cancelling the Health Council of Canada — an independent, public reporting agency — has limited our ability to understand and make informed changes to national healthcare standards and delivery. Refusing to conduct a national inquiry on murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls has prevented us from understanding the full scope of the problem and allowed the government to minimize the issue. Reducing press access to the Prime Minister and Cabinet Ministers has resulted in a dependence on partisan talking points, as opposed to open dialogue with our elected representatives.

To say that the Harper government makes uninformed policies is false. The policies are informed, but by polling numbers rather than policy research. On contentious issues such as climate change, harm reduction, and criminal law, the Harper government has consistently ignored research which contradicts their policies. For example, Vancouver’s Insite safe injection site has proven successful in reducing deaths and rates of HIV/AIDS infection, while increasing the likelihood that users will access addiction treatment, and without contributing to an increase in crime. Yet the government has tried to prohibit Insite from operating and made it virtually impossible for communities to implement similar facilities on the grounds that they encourage drug use and endanger families. Harper’s insistence on treating drug use as a criminal issue, rather than a health issue, betrays a close-minded tendency to pursue ideological values at the expense of pragmatic or evidence-based policy.

The Harper government has spent the last decade trumpeting a need for criminal justice reform. This is in clear disregard to research that has consistently shown that crime rates in Canada have been in decline since the 1990s (similar to the U.S. and other industrialized countries) and are not impacted by punitive criminal justice policies. The results of Harper's tough-on-crime agenda has not been a safer Canada, but it has increased the rate and severity of imprisonment, particularly for Indigenous and impoverished people.

As for climate change, it is again a story of stubborn disregard for the consensus in the scientific community on both the current state of affairs and on actions we could take to prevent further deterioration.

So we find our government, at best, making important decisions based on limited access to information perpetuated by their own policies. Or, at worst, making decisions that contradict comprehensive, respected research on the health and safety of Canadians, particularly those groups that are marginalized and vulnerable, in order to score political points.

At home and abroad, our government has paired noisy rhetoric with hollow policy.

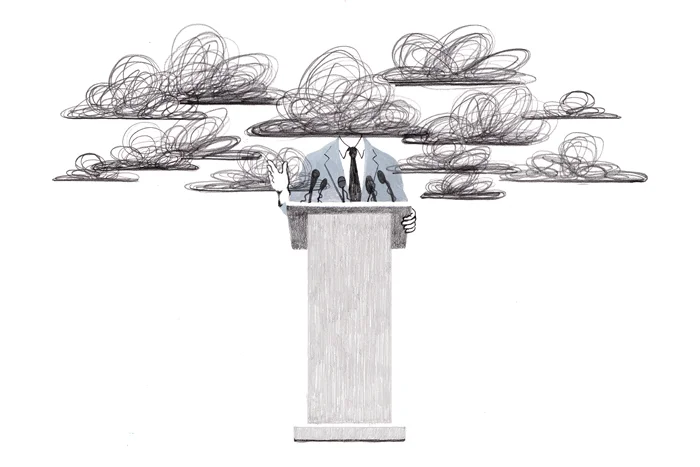

One of the defining changes of the Harper era involves the emergence of the “permanent campaign” and “wedge politics.” These terms describe the way in which the majority of contemporary political activity and governance is designed to bolster political support for the Conservatives and to galvanize the party’s base through hyper-partisan, polarizing decision-making. As a result, many of the defining moments of the Harper decade have centered around changes in rhetoric and the introduction of bills designed to make a political statement. This empty style of governance distracts us from making real changes that benefit Canadians, paving the way for politics that prey upon our worst instincts of self-interest, xenophobia, or racism.

Take, for example Bill C-51, which, among other violations of rights and freedoms, expands the categories of personal information that may be collected, analyzed, and shared by the government. Bill C-51 passed despite evidence suggesting it would be ineffective at best and actively deleterious at worst, but it was welcomed by the Conservative base and succeeded in dividing Canadians. In general, surveillance policy under the Harper government has been marked by inflated threats and “excessive” responses, which have culminated in an increase in the powers of state organizations to investigate and interfere with the lives and views of Canadians.

Crime policy has been an area of perennial concern for the Harper government and its base. In 2014, Public Safety Minister Stephen Blaney suggested that all convicted criminals (even those convicted of minor offenses) should be imprisoned — but no one believes that is actually possible. The government has also passed empty bills on sentencing and the protection of police animals which will have almost no practical effect on the judicial process. The Harper government has implemented a number of substantive crime bills, but it is just as often rhetoric and public messaging that have altered the purpose and nature of our judicial process in the eyes of Canadians. Policies that encourage rehabilitation and reintegration have been all but subsumed by the need to punish and imprison.

Canada’s commitment to foreign aid has also been hollowed out. While ostensibly we continue to support efforts to reduce global poverty, the merger of the standalone Canadian International Development Agency into the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade represented the Harper government’s transformation of foreign aid into a mechanism for resource development. Countries that accept our aid, now must also accept the presence of the Canadian extractive industry, often including companies with a history of human rights abuses and failure to comply with environmental standards.

While foreign affairs is a policy area where reliance on rhetoric is common, critics argue that the Harper decade has been marked by foreign posturing and domestic pandering at the expense of good diplomacy and our international reputation. We can point to many examples — the extravagant, unconditional support of Ukraine springs to mind. Harper’s proclamation was welcomed by the large diaspora of Ukrainian Canadians, but dismissed by international powers as bluster from a military lightweight. Or Israel – where Canada’s official stance on issues such as Israeli settlements in occupied territories, the status of East Jerusalem, or the rights of Palestinian refugees to return, has not changed, but Harper’s public statements and Canada’s staunch support of Israel at the UN suggest we are fully aligned with the most right-wing government in Israeli history. Harper has also taken action to negate criticism of the state of Israel at home, even accusing detractors of anti-Semitism. Commentators are quick to note that Harper’s noisy and controversial rhetorical posturing in the Middle East has not only damaged our international standing, but has helped to entrench the mutually destructive status quo in Israel/Palestine.

Though Canada has changed, it is our belief that Canadians have not.

Ten years on, the Conservative party’s finely crafted and meticulously calculated campaign has begun to show cracks, revealing a suffocating dependence on fear, callousness, and blinding self-interest.

Canadians are looking for a different approach. One that embraces diversity and understands what we can achieve together. One that recognizes social inequality to be a real problem that requires our collective efforts to solve. One that does not project fear of the unknown but explores possibilities with a sense of optimism and ingenuity.

On Monday, it is our hope that others will feel the same, and choose to reorient our nation towards a more inclusive, tolerant, and imaginative future.